By Thomas M. O’Toole, Ph.D.

An important lesson I have learned from observing jurors’ decision-making in mock trials is that jurors sometimes dislike strategies that nevertheless are quite effective. They may not like what they see, yet they are still persuaded by it. These moments can be tough to digest. Besides the gut-check, it is difficult to ignore the fact that several mock jurors are criticizing something you did. However, research has shown over and over again that persuasion does not always happen at a conscious level. In other words, what jurors verbally express about something does not necessarily reflect its actual effectiveness.

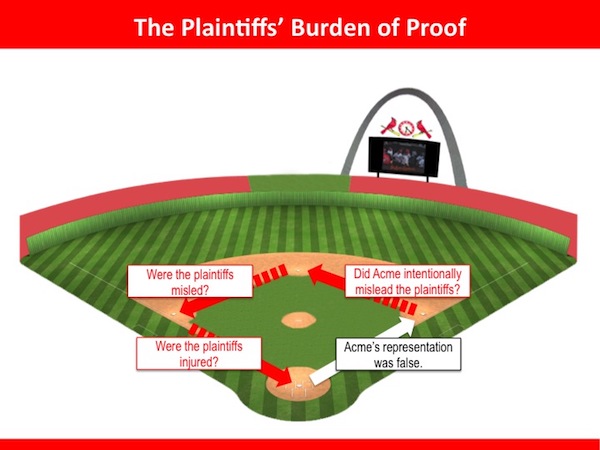

A great example of this is a graphic that we created for the defense in a case a few years back involving claims of fraud. This case was particularly challenging because the judge had ruled ahead of trial that the defense had misrepresented the only issue in question. We had the difficult task of trying to get jurors focused on the remaining elements of a fraudulent misrepresentation claim. We had to find a way to convince jurors that the judge’s ruling was not that big of a deal…that it was not the death knell for the case that it seemed to be.

Notably, this trial was in St. Louis, Missouri, where I was born and raised for most of my youth. There are three things that define St. Louis, Missouri: 1) Toasted ravioli (one of the greatest foods of all time); 2) Everyone who lives there wants to know what high school you went to; and 3) the St. Louis Cardinals. St. Louis is a serious baseball town. The fans will brag that it is the greatest baseball town in the country. The Cardinals are important to St. Louis in so many ways that go well beyond the space available in this blog post.

Due to the importance of baseball in St. Louis, we developed an important analogy and graphic. Our analogy was that the judge’s ruling that there had been a misrepresentation on the central issue in the case was equivalent to hitting a single in baseball. It was a hit in an important game, and no team likes to give up hits, but it was meaningless in and of itself. We argued that the plaintiff had to prove the other elements to get that runner on first over to second, then over to third, and then to home before the jurors could count it as a score. We developed an animated version of the above graphic to visually reinforce this argument.

Since there was significant exposure associated with this case, we conducted mock jury research in advance of trial. We used the analogy and graphic in the mock jury presentation. All of the group deliberations started the same: the mock jurors hated the analogy and ripped it apart. They felt it was pandering and manipulative. Many mock jurors made comments along these lines right out of the gate. Frankly, it was embarrassing to sit in the closed-circuit room with the trial team and general counsel to whom I had recommended this analogy and graphic.

I sank back into my chair, terrified of the beating to come over the remaining three hours of deliberations. However, as we watched deliberations unfold, despite the hatred the mock jurors had voiced about this analogy and graphic, they still used it. We heard mock juror after mock juror describe the judge’s ruling as a single. We heard them talk meaningfully about the other elements of the claim and the plaintiff’s burden to independently prove each of those elements…to get to second, on to third, and then on home to score the run. They said they hated the baseball analogy, but they used it repeatedly when they talked about the issues. They were vocal about their view that it was pandering, yet they used it in their decision making. In the end, we won on the other elements of the claim with some serious help from this analogy. We had given our advocates on the mock juries an easy way to downplay the importance of the judge’s ruling and the plaintiff’s advocates in the groups did not know how to respond.

This all speaks to an important lesson in jury decision-making: what they say is not always as important as what they do. This is a critical reminder, because when you are observing mock jury deliberations, what they say is obvious and easily accessible. What they are actually doing requires you to dig a little deeper – beyond the words – as that is where some of the best strategies are found.