This past week, King County Superior Courts in Seattle, Washington laid out their plans for the resumption of civil jury trials. In an effort to avoid having large groups of jurors in the same place, jury selection will be conducted mostly over Zoom, which is a fascinating development that should cause many to rethink their jury selection strategy. However, the court has also noted that it intends to rely on the expanded use of supplemental juror questionnaires, though the parameters will likely vary from case to case and judge to judge. We have seen a lot of different supplemental juror questionnaires used by courts across the country ranging from a half-page sheet with almost no useful information to 47-page questionnaires with so much information that it was difficult to analyze in the time that we were given.

I suspect that King County is not alone in its expanded use of juror questionnaires during the COVID-19 pandemic, so this week’s post will focus on tips for creating useful supplemental juror questionnaires. For me, “useful” means the questionnaire provides a lot of valuable information about your potential jurors in a format that is easy to quickly gather and analyze information. There are a variety of factors that impact the usefulness of the questionnaire including the questionnaire format, types of questions, and the language used throughout.

Prior to the pandemic, my advice to attorneys seeking court approval for the use of supplemental juror questionnaires in civil matters was almost always the same: 1) keep it short; 2) reach agreement with the other side before presenting it to the judge; and 3) make it as easy as possible from a logistical standpoint to administer.

Most of this advice still applies. The questionnaire should be reasonably short when examined against the case. For example, an automobile injury case that is only going to last three trial days does not need a 47-page questionnaire and trying to get one will likely frustrate the judge, which is not helpful and could have a spillover effect onto other case issues.

It is also helpful to reach agreement with the other side before submitting the questionnaire to the judge. In my experience, when there is disagreement over particular questions in a questionnaire, the judge often just removes those questions, which provides both sides with less information about the potential jurors. By working with the other side, perhaps the wording or format of the question can be altered to make each side happy. Alternatively, there may be some give and take where one side agrees to a set of questions that it wants if the other side is willing to do the same on another set of questions.

With more courts opting to use supplemental juror questionnaires, it will still be important for each side to understand the logistics of how these questionnaires will be administered and how the responses will be collected and provided to each side. Since some courts or judges will be new to the process, attorneys could have an opportunity to shape the process in a beneficial way. For example, the parties might encourage the judge to allow more time between the administering of the questionnaire and the actual voir dire follow-up so that there is ample time to conduct a thorough analysis and draft follow-up voir dire questions. If, however, there will not be much time to analyze the responses, the parties may want to opt for a shorter questionnaire or at least a format that allows for much quicker analysis.

If you have been following our blog over the years or have read some of our other publications, you know that we believe the most important information to collect about your potential jurors relates to attitudes and experiences. These are most predictive of human behavior and decision-making. Demographics are certainly relevant in some cases, but we often assume demographics are relevant because we assume people of similar demographics have similar attitudes and experiences. If this is the case, why not cut to the chase and just ask directly about those experiences and attitudes?

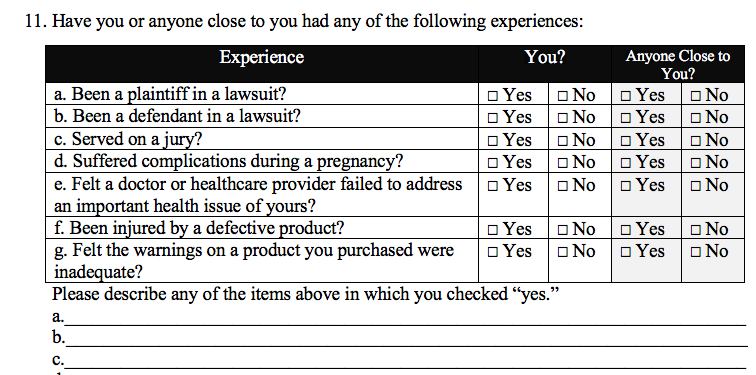

For experience questions, these are pretty straightforward, but there is some formatting that can help make these easier to analyze when all of the responses come back. We typically like to group the experience questions all into one place like in the following example:

This format is helpful because it shortens the amount of space required on the questionnaire to ask the questions, which allows for more questions. The check box columns also allow the trial team to quickly look down the section and identify instances where the “yes” box was checked. This allows for much quicker analysis than the way experience questions are typically formatted in supplemental juror questionnaires.

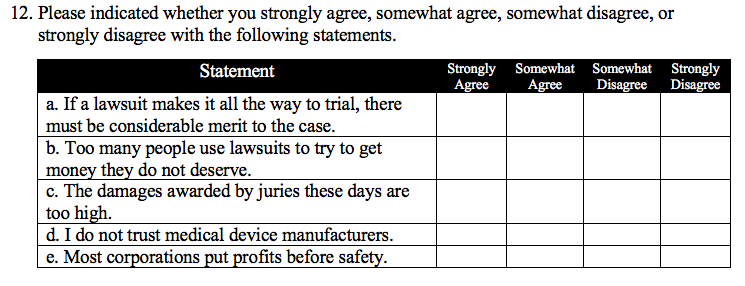

For attitude questions, we like to use a similar grid with a Likert Scale (i.e. strongly agree, somewhat agree, somewhat disagree, strongly disagree) format as in the following example:

The Likert Scale format is helpful and fair because it is not one-sided. All parties can see whether potential jurors agree or disagree with each of the statements. Sometimes there is debate about whether or not potential jurors should be provided a “Don’t know” option, but this option does not provide useful information to the attorneys. Instead, I prefer that venire members are forced to pick the option that is closest to their opinions.

These Likert Scale attitude questions are usually where we have the most controversy with the other side. Some attorneys mistakenly conclude that we are trying to “sell the case” with the attitude statements, but that is really not the case at all. Instead, we are just trying to get a picture of the underlying beliefs in the jury pool since we know that jurors will reject evidence and arguments that go against their beliefs. Consequently, these kinds of Likert Scale questions are useful for both sides. We often let opposing counsel add some of their own attitude statements so that they feel like there is more “balance” in the questionnaire.

Finally, these formats are also easy for the potential jurors to navigate. Jurors generally do not enjoy filling out lengthy questionnaires that require them to write a lot. When asked to do so, many will not provide complete answers or provide the information that the attorneys are seeking. These simple grids help avoid that problem.